The many ways of narrative design in multiplayer games.

Hello hello! After writing the previous blog post about consumables, I realised that it was quite fun to write down my thoughts about the thing I am passionate about – game design. While looking for feedback, I received a suggestion to analyse played multiplayer games and the narrative design in them. And when I started to look back at all the experiences that I had, I understood why: players being able to see and interact with each other can lead towards some interesting and creative narrative design decisions.

From the way I see it, narrative can be split into two categories. Story based, for example, help monkey get their lost banana back and then kill monkey-god. And emergent narrative, for example, imagine a player telling their friend how they were playing a decisive round in a ranked match, when suddenly all 4 of their allies got killed with the opposing team still being full. But miraculously, the player managed to take their enemies. One. By. One. Thus pulling an amazing clutch and winning the game. Quite the story!

While I am curious about the emergent narrative and would like to explore it further, in this blog post, I would like to explore the story orientated design and look at things to consider when trying to integrate having more than one player into their stories and how the stories can be explored both from within and outside the game.

Player’s role within the narrative

In single player games players can experience the narrative through the environment, codex entries, NPCs, audio logs and the such. Multiplayer games can also do that, but they also have another precious resource – the other players. The extra players can help convey multiple feelings, such as camaraderie, or accent the feeling of isolation after leaving a bustling hub area and then exploring a desolate world. And since there are a lot of different narratives that include multiple players, there are also multiple things to consider.

The ability to interact and solve problems together is what makes the multiplayer games. Without this ability, the games would be just single player games in a shared space. Interaction is solved differently in games. In MMOs, for example, it comes through player roles, like tanks, healers and DPSes. And the ability to work together is tested in dungeons or raids – special areas, where players have to work together in order to survive and clear the challenge, netting them precious loot. This structure is successful enough for it to be also used in story missions and not only as optional content. For example, in Guild Wars 2 a good chunk of the personal story questline was spent on preparing for the fight against Zhaitan, an elden dragon, with the final quest being the showdown between it and the protagonists. Initially, this fight was a raid, which through group coordination requiring difficult challenges, conveyed how strong was this final boss and that the player did not prepare for nothing. But there are more cooperation driven narrative examples. Like how in It Takes Two, the two players play as a husband and wife, who were about to get divorced, but after getting transformed into dolls are working together to go back to normal. Spoiler alert, but throughout the game protagonists eventually manage to rekindle their relationship and turn back to humans. The story would not be as impactful if all the players did was mow down hoards of gnomes with machine guns, as it would not really match the story. But making players face challenges that they can solve only by communicating with each other aligns very closely with the story’s protagonists mending a relationship on a verge of collapse by talking and working things through. This alignment lets the player relate with the characters and further immerse themselves into the story. Therefore, findings ways to use players cooperation as a way to convey the narrative beats can help enhance the experience.

Just having a bunch of players running around doing their tasks can already help make the world feel lively, which is further enhanced by the ability to converse with each other. Personally, I fondly remember striking up conversations with random people, while cutting down willow trees near Draynor Village in Runescape. These kinds of interactions are what make MMOs feel special for me. However, this liveliness is not always ideal when trying to convey a more serious narrative beat. Imagine, after the player defeats a massive golem, rescues a friend and then returns to a nearby village, the camera pans to show a mysterious masked figure silently observing our protagonist from afar. This creates mystery and suspense. But now imagine, if a random player just appears in the background, starts running and jumping around and then finally starts mining some ore. Tension and intrigue? Most likely gone. That is why MMOs, like Final Fantasy XIV, that I borrowed this scene from, create separate instances, which are populated only by the protagonist and their party, thus no random elements, that could ruin the moment, appear. Guild Wars 2 takes this idea even further, by displaying the more important conversations as two characters standing in front of each other, with an appropriate stylish background to hide potential disruptors. Which helps the player immerse themselves into the dialogue instead of having concentration broken by many moving objects around. Furthermore, in Tom Clancy’s The Division the game world is split into two categories: the hub areas and the play space. In the hub areas players can meet each other, interact and party up, but once they leave into the play space the only humans they encounter are enemies. This separation really helps to convey that there are a bunch of agents trying to save the day, but the post-apocalyptic world, they find themselves in, is vast, eerie and full of hostiles. While having multiple people share space and interact within it is a lifeblood of multiplayer games, it is always good to consider ways of isolating the protagonist and how can that help to convey the narrative better.

Often characters will have unique looks, movements and voice lines that can give insight into their background. Let’s look at Junkrat from Overwatch. Spikes, bombs, twitchy movements – all point to high-octane and explosions loving character. And faces are especially good at giving us insight about the mannerisms of said character. Matter of fact, while covering internal models in “The Art of Game Design”, Jesse Schell mentioned that our minds store a lot of data about heads and faces, because so much information about a person’s feelings come from them. This information helps us feel empathy and perceive anything representative of a human, like a cartoon character. But sometimes, having no defining characteristics or face can also help tell a story. In Helldivers 2 the player take the role of helldivers, elite forces of the Super Earth sent across the galaxy to spread “managed democracy”. Beneath the very intentionally ironic façade of democracy and freedom, lies an authoritarian regime, that spares no life or resource in its endless war to establish human dominance over the galaxy. The helldivers always wear masks, are cryogenically frozen after completing their training, and unfrozen only when they are needed in the battlefield. This kind of robbing of characteristics, sells the feeling of being just a tiny and very replaceable cog in a gargantuan war machine. Therefore, it is worth asking how unique does the player character really need to be when conveying various narratives.

Like mentioned before, in some games like The Division, there sometimes is a need to create a hostile and empty feeling world. Which can be done by limiting the amount of friendly players one sees. But there might also be a need to convey the feeling of people working together to overcome said world. And for that, having other players is not even necessary … as long as they are replaced by an intractable artifact that they themselves have left behind. These artifacts can take many shapes and forms. For example, in Death Stranding, the player can see built structures, left behind vehicles, messages and lost pieces of cargo that were left there by other players in their own games. The player can interact with these artifacts by sending likes to the owner, using, picking up, or fixing them. These artifacts and, most importantly, meaningful interaction with them, as they can affect how the player plays, create a sense of asynchronous cooperation. This type of coop works well with the narrative that there are more porters, just like the main protagonist, delivering valuable cargo, while also letting the player experience moments full of calmness and peaceful solitude, such as when approaching Port Knot city for the first time. Async coop is also present and used to great effect in Elden Ring and Dark Souls games. In these games, players can leave messages for each other. They usually contain warnings about upcoming powerful foe and directions towards a hidden treasure, some give instructions to jump off a cliff to a certain death. While others show how flexible the messaging system and languages are by containing puns or fandoms inside jokes (deciphering “Mist or Beast” and “Fort, Night” is left to the reader as an exercise). This type of communication is what sets the mentioned FromSoftware’s games from any other soulslike game that I have played, at least for me. Sure, the worlds are big, scary and filled with many more powerful enemies that find no trouble in vaporizing me. But finding a message that warns me about an enemy on left side of a tunnel or hidden wall, makes the whole experience less about me vs the world and more about a common struggle between many tarnished (and chosen undead, and curse bearers, and ashen ones). Which is one of the main narrative points within Elden Ring and Dark Souls games. Thus, it is worth considering what kind of cooperation helps to express the story we want to tell the best and do the players really need to play together at the same time in order to achieve a common goal.

Players are the main drivers of the story, and having more than one requires further considerations when designing the ways said players will experience the narrative. If players share the space, then think how can they be isolated. But if players act as individuals or small parties, then how can players be made aware of the rest of the players and do they need to be play together at the same time, or is it enough to only convey the feeling of playing with others through artifacts. And how can the setting be expressed through visuals of the players.

The living world

Environmental storytelling is a great tool to convey portion sized stories to the player that takes their time to look and explore the world. But live service multiplayer games, through the need to give the players something new to explore, have a chance to elevate it to another level.

To give players something new and exciting to enjoy for a limited time (ethics of FOMO is beyond the scope of this blog post) some games run specialised events. Some of these timed events can align with real life holidays, such as Christmas or Lunar New Year. But there can also be events dedicated to some in game lore. For example, in Apex Legends, a battle royale with numerous unique heroes, back in Season 2 there was a Voidwalker event, dedicated to one of the heroes – Wraith. During this event, a named location was transformed: a sealed door was opened and a massive portal above the place was added. Furthermore, if Wraith was in a party, she would often make comments about the place and her past or receive questions from other player’s heroes. This event brought a burst of novelty to the map and let the players explore the backstory of one of the most popular characters. Additionally, the same map location was also used to foreshadow a new character by the end of the same season. However, this concept can be taken even further. While the smaller location changes were perfect for a few week events, Apex Legends also brought massive map changes to it’s maps for every new season, that takes around 90 days. For example, Kings Canyon, the very first map, received massive changes throughout the seasons, like how in season 2 the map was invaded by the local wildlife and in season 5 an explosion replaced two very popular locations with a massive crater. Of course these changes did not just happen out of nowhere, they followed promotional videos that showed what happened to lead to these alterations, but more on that later on. Overall, maps do not have to be static, they can change, and this change can be used to create and tell stories.

While talking about storied being told through the game maps and their changes, it would be weird not to mention Fortnite and it’s Live Events. These happen only once, at a certain time, and throughout every played match. The scope, the server load and the engineering behind it still amaze me and are probably expensive enough that only a few studios can do it. Nonetheless, it’s still an amazing thing, that is worth talking about. While some of these events were used for real time concerts, plenty of them were used for narrative reasons. Most notably, on 13th of October 2019 every player was sucked into a black hole, which then swallowed up the entire map. Which was then followed by a black screen, players being locked out of the game and Fortnite’s social media’s profiles starting to use a black profile picture with their posts becoming hidden. This certainly created a lot of buzz around the internet, with people trying to guess what happened and what comes next. Eventually this led to the start of new chapter of the game. While most likely unfeasible for most of us, Live Events are certainly a really cool way of telling a story in a live service game.

If a game was created to be played for years and there is a need to give players a reason to come back. Some kind of changes will be needed. Balance adjustments or new weapons can certainly be part of it. But changes to the maps that players share space in, can be very noticeable and bring a lot of sense of novelty. So why not consider how these changes can be used to create a larger over-arching narrative, that could be one more reason for the players to return to the game.

When the action is too hot

Having a conversation with an NPC about a nearby anomalous zone that consumes all sound and data within it while in a disco church is certainly a way to explore the world building and the game’s story. But in some multiplayer games, being locked into a conversation might not really work. The main problem arises from the fact that not everyone wants to participate. In a PvP game, being locked out of the combat or being distracted can mean the opportunity for the opposing team to score. In a coop PvE game, playing with random people can lead to a scenario where one person has never experienced the story, while the other teammate has already memorised the dialogue lines. But there are ways around that.

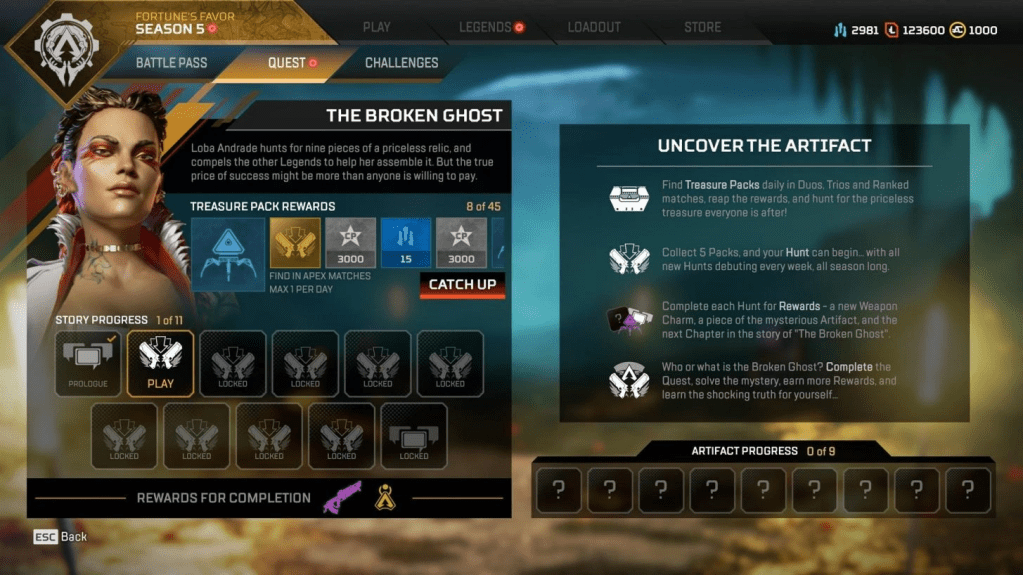

In games with a more time sensitive or a very intense match, the opportunity to explore the game stories lies within the downtime between the matches. With “matches” being used in a more broad sense to describe a time period from the start to the victory or defeat screen. For example, in the base game of World War Z there are four episodes containing separate stories. Each episode is split into chapters and before every chapter there is a small cutscene, which explains where the four heroes are, how they ended up there and what do they need to do. These bite sized drops of narrative are great at setting the scene of the match and then letting the story unfold through the objectives. This setup can also work in a PVP games, like in Titanfall 1 story mode, which was basically just a list of regular multiplayer matches, just with a different intro playing in it. Also, in World War Z, players can unlock short animated movies for the hero characters if they finish the whole episode with one of them. Which is another good way to explore the world and it’s characters in between the action, while also adding motivation to replay the game’s levels. There are also ways to integrate unlocking the story into the high-octane gameplay, such as in Apex Legends. Starting from season 5, once a day, players could find a treasure pack that would drop when openning a chest, an action that players will be constantly do during their match. Collecting it would grant a small reward or access to PvE mission or a comic page, which explored the season’s story. This is a very elegant solution, as it incorporates a chance to unlock a bit of the story while playing game regularly and gives players a reason to return to the game the next day.

Helldivers 2 also explores the narrative in between the matches, but in a slightly different way. In HD2 players do not have a traditional story quest to follow, instead players can contribute to a shared objective, called Major Order. These objectives are relatively simple, like kill X amount of K enemies, or defend Y planet, and they can be easily contributed to by just playing within the specified regions. This is also a great way to make players engage with different enemy factions, as these orders usually jump between them. The orders themselves are delivered through a text pop up. While simplistic, its flexibility allows the game master, Joel, to react to successes or failures of the players and evolve the story accordingly. Therefore, if the game’s action is a bit too intense, it is worth to consider how the time leading up to said action can be used for telling the narrative.

In order to experience the story while in a match, players need to be able to do so independently and have moments with less action. For example, in Overwatch, and it’s 5v5 battles, this would be very difficult to achieve due to constant fighting. But by allowing players to dictate their own pace, opportunities arise. Like in extraction shooters, such as The Cycle: Frontiers, in which players explore a massive map and can choose to be aggressive and hunt other players for their gear, or take a more passive approach and sneak around, loot containers and fight local creatures. The ability to choose the more passive approach is what allows players to complete various missions, like finding certain materials or depositing quest items into specialised containers. A similar choice is also present in Call of Duty Black Ops zombie modes, in which players fight through increasingly difficult waves of zombies while buying up perks, weapons and unlocking new areas. In Zombies, the narrative is explored through completely optional easter-egg type tasks. Players who want to just grind through waves upon waves of zombies can do so, while players who would like to take a crack at story can do so by shooting a few zombies into their feet, slowing them down and effectively delaying the next wave of enemies for as long as the crawling zombies are alive. In this case, working together ensures survival, but it is possible for both players to share the same space. By creating opportunities for players to decide on the intensity of the action, we can let them experiences the games’ story while in the match.

In some games, locking a player or their whole party for a story bit might go against the core design of the game, but there are still opportunities to explore the narrative. Such as doing so while the player is taking a break between the intense matches, or giving the players ways to slow down the action and then explore the story.

Transmedia

Games stories do not have to be told only within the game, they can also be told outside the game’s bounds – through videos, comic books or even secrets hidden all around the internet. While this approach can be done by both multiplayer and single player games, personally I think multiplayer, especially live service, games do this more often to keep players engaged for longer.

Short videos, such as trailers before the game launch, can serve as great marketing materials. They are flashy, show what the game is about, and can be easily shared through social media. Live service games also have these, and not only before the original launch, but also before any major update. For example, before releasing a new character, some games would hype them up by releasing an announcement trailer, which would show the character’s backstory. I remember seeing the trailers for new Apex Legends characters, getting super excited and instantly sharing them with my friend, who I played it with. Or, alternatively, some stories within the Team Fortress 2 universe were told through comics that were being released since 2009 with the latest one in 2024. There are also other formats such as CD dramas or even stage plays that were used for exploring the world of Nier games, or full on TV shows like Arcane that starred some of the characters from League of Legends. There are many different ways, some more accessible and sharable than others, of telling the games’ story outside the game and it might be worth considering them if exploring them during the game gets too difficult.

Alternate reality games (ARGs, but not to confuse with augmented reality games, so maybe AlRGs?) are games hidden within the real worlds with one puzzle leading towards another. Solutions to these puzzles can involve things like cryptography, spectographic analysis of audio tracks, or glueing various bits of text together into a URL. Because of the difficulty, these can evolve into community projects. Some videos games can also employ these puzzles to tell a story, generate excitement or give some kind of clues for upcoming developments. Such as, Helldivers 2 having the Station 81 ARG event hosted in their community Discord and on YouTube, which ended up revealing an enemy faction fleet invasion. Or how the true ending of Inscryption, and potential contribution to the overarching narrative of the developers games, was reached only through ARG which involved codes hidden in videos within the game and digging out floppies in the real world. While the thought and the setup might require resources, community-led ARG can be a great reason for the dedicated players to come together and uncover secrets of the game’s world.

Story telling through alternative forms is pretty rare and is usually, but not always, done by a higher budget studios, but that should not be a reason to not consider them, as they can still come as a great source of inspiration.

Final words

There is a plethora of different multiplayer games, each with their own design goals, budgets sizes and stories to tell. Which results in countless considerations on how to integrate said stories into the games, while also keeping in line with rest of the games systems, but I hope that this blog post gave you some food for thought. And I know that there are a bunch of other games that do this in some very cool and unique ways, and if I get to play them, I will make a part 2 or update this one, since this topic is definitely broad!

See ya next time!

– M

Personal Note

I had a bunch of fun reminiscing about the games that I have spent countless hours in. And while doing so, I remembered two tracks that have stuck with me for a while. First, the Forsaken theme from Destiny 2, which would play at the login screen. The brass section at the beginning hyped my up and made me excited about the session I was about to have. And the second track is “Your decisions make you” from Warframe played at the end of The War Within quest really pulled my emotional strings when I heard it.

I would really love to play more of these two games, since there is so much I have not touched, but there is so little time and so many other games to try, enjoy and analyse T.T